https://phtq-canada.blogspot.com/2021/12/2-dai-toi-ac-cua-dao-thien-chua.html

Crusades & Exorcism

Trong lịch sử nhân loại, đạo Thiên Chúa tạo ra rất nhiều tội lỗi, tội ác khủng khiếp. Đó là:

1. Thập Tự Chinh (Crusades)

2. Trục Hồn Quỷ Nhập - Mê Tín (Exorcism)

Cho đến ngày nay, tại xứ Nga RUSSIA, các giáo sĩ thờ Chúa vẫn còn làm phép trên vũ khí giết người. LINKs:

RUSSIA Đặc sắc nghi lễ ban phước cho vũ khí của Quân đội Nga

http://phtq-canada.blogspot.com/2017/01/ton-giao-la-me-tin-gat-gam-cac-giao-si.html

http://phtq-canada.blogspot.com/2018/08/theo-chinh-tri-theo-ton-giao.html

http://phtq-canada.blogspot.com/2020/02/gat-gam-trong-nha-tho.html

|

| the-disastrous-time-tens-of-thousands-of-children-tried-to-start-a-crusades-featured-photo |

llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll

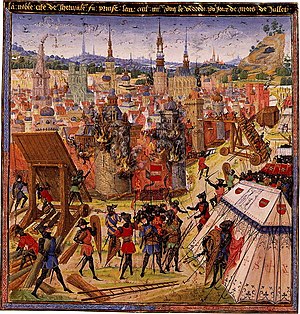

Thập tự chinh - Crusades

Thập tự chinh là một loạt các cuộc chiến tranh tôn giáo, được kêu gọi bởi Giáo hoàng và tiến hành bởi các vị vua và quý tộc là những người tình nguyện cầm lấy cây thập giá với mục tiêu chính là phục hồi sự kiểm soát của Kitô giáo với vùng Đất Thánh. Quân thập tự đến từ khắp Tây Âu, và đã có một loạt các chiến dịch không liên tục giữa năm 1095 và 1291. Các chiến dịch tương tự ở Tây Ban Nha và Đông Âu tiếp tục vào thế kỷ XV. Các cuộc Thập Tự Chinh được chiến đấu chủ yếu giữa người Giáo hội Công giáo Rôma chống lại người Hồi giáo và các tín hữu Kitô giáo theo Chính Thống giáo Đông phương trong Byzantium, với các chiến dịch nhỏ hơn tiến hành chống lại người Slav ngoại giáo, Balts ngoại giáo, Mông Cổ, và người Kitô giáo ngoại đạo [1]. Chính Thống giáo Đông phương cũng tham gia chiến đấu chống lại lực lượng Hồi giáo trong một số cuộc Thập Tự Chinh. Thập tự chinh được thề và đã được cấp một ơn toàn xá bởi Đức Giáo hoàng [1][2].

Các cuộc Thập Tự Chinh ban đầu có mục tiêu thu hồi lại Jerusalem và Đất Thánh khỏi ách thống trị của Hồi giáo và các chiến dịch của họ đã được xuất phát từ lời kêu gọi của các nhà lãnh đạo đế chế Byzantine để được sự giúp đỡ nhằm chống lại sự mở rộng của người Thổ Seljuk theo đạo Hồi tới Anatolia. Thuật ngữ này cũng được sử dụng để mô tả các chiến dịch đương thời và sau đó được thực hiện ở thế kỷ XVI ở vùng lãnh thổ bên ngoài Levant [3], thường là để chống lại ngoại giáo, và nhân dân bị khai trừ giáo tịch, cho một hỗn hợp của các lý do tôn giáo, kinh tế, và chính trị [4]. Sự kình địch giữa các quốc gia Kitô giáo và Hồi giáo đã dẫn liên minh giữa các phe phái tôn giáo chống lại đối thủ của họ, chẳng hạn như liên minh Kitô giáo với Vương quốc Hồi giáo của Rûm trong cuộc Thập Tự Chinh thứ năm.

Các cuộc Thập Tự Chinh đã có một số thành công tạm thời, nhưng quân Thập tự cuối cùng bị buộc phải rời khỏi Đất Thánh. Tuy nhiên các cuộc Thập Tự Chinh đều tác động từ chính trị, kinh tế và xã hội sâu rộng ở châu Âu. Bởi vì các cuộc xung đột nội bộ giữa các vương quốc Thiên chúa giáo và quyền lực chính trị, một số cuộc thám hiểm thập tự chinh đã chuyển hướng từ mục tiêu ban đầu của họ, chẳng hạn như cuộc Thập Tự Chinh thứ tư, dẫn đến sự chia cắt của Constantinopolis Thiên chúa giáo và sự phân vùng của đế chế Byzantine giữa Venice và quân Thập tự. Cuộc Thập tự chinh thứ sáu là cuộc thập tự chinh đầu tiên xuất phát mà không có sự cho phép chính thức của Đức Giáo hoàng [5]. Các cuộc Thập Tự Chinh thứ bảy, thứ tám và thứ chín đã dẫn đến kết quả là chiến thắng của Mamluk và triều đại Hafsid, như cuộc Thập Tự Chinh thứ chín đã đánh dấu sự kết thúc của cuộc Thập Tự Chinh ở Trung Đông [6].

Bối cảnh, nguyên nhân, động cơ

Khoảng thế kỷ thứ VII, những người đứng đầu đạo Hồi tiến hành các cuộc trường chinh xâm chiếm các vùng đất mới. Từ năm 660 đến năm 710, các giáo sĩ Hồi giáo đã chiếm được một lãnh thổ rộng lớn ở Bắc Phi, Thổ Nhĩ Kỳ. Đến năm 720, những kỵ binh Hồi giáo chiếm Tây Ban Nha rồi thọc sâu vào đến tận lãnh thổ Pháp; từ năm 830 đến năm 976 Sicilia và miền nam Ý rơi vào tay người Hồi giáo. Lúc này, những đoàn hành hương của tín đồ Kitô giáo về các miền Đất Thánh mà trong đó Palestine là nơi thiêng liêng nhất bắt đầu phổ biến từ thế kỷ IV và đến thế kỷ XI đã trở nên rất thịnh hành. Người Thổ Seljuk Hồi giáo không cố ý ngăn cản những đoàn hành hương nhưng họ thu rất nhiều loại thuế, phí gây ra làn sóng phẫn nộ trong cộng đồng Kitô giáo[cần dẫn nguồn].

Cũng sang thế kỷ XI, Đế quốc Byzantine (Đế quốc Đông La Mã) chỉ còn lại một vài vùng đất ở châu Âu. Lúc này, nguy cơ người Hồi giáo tràn sang phía Tây đã hiện hữu đối với người Kitô giáo đặc biệt là sau khi quân đội Seljuk đánh bại quân Byzantine trong trận Manzikert năm 1071 và bắt được cả hoàng đế Romanus IV thì con đường tiến về Constantinopolis đã được khai thông. Suleyman, một thủ lĩnh người Thổ Nhĩ Kỳ và các chiến binh của ông thậm chí còn định cư ngay tại Niacea, chỉ cách Constantinopolis vài dặm. Để giành lại các vùng đất đã mất ở Tiểu Á, Hoàng đế Byzantine kêu gọi sự giúp đỡ từ phía Tây nhưng không có kết quả. Sau đó, họ kêu gọi sự giúp đỡ từ Giáo hoàng và để đổi lại, họ hứa sẽ xóa bỏ sự phân ly giữa Chính thống giáo Đông phương và Giáo hội Công giáo Rôma xảy ra năm 1054. Ngày 27 tháng 11 năm 1095 tại Hội nghị giám mục, Giáo hoàng Urban II (tại vị 1088-1099) kêu gọi các hiệp sĩ, hoàng tử phương Tây và tín đồ Kitô giáo đến giúp đỡ tín hữu Kitô giáo phương Đông đồng thời giành lại những vùng Đất Thánh đã mất.

Mặc dù những cuộc thánh chiến mang đậm màu sắc tôn giáo, nhưng giới sử học cho rằng bên trong nó còn có các động cơ kinh tế, chính trị, xã hội:

- Tôn giáo: việc thánh chiến để bảo vệ và lấy lại những vùng đất của người Kitô giáo được hậu thuẫn bởi thay đổi quan trọng trong phong trào cải cách Giáo hội đang diễn ra. Trước khi Giáo hoàng Urban II phát ra lời kêu gọi, quan niệm Chúa sẽ thưởng công cho những ai chiến đấu vì chính nghĩa đã rất thịnh hành. Công cuộc cải cách của Giáo hội đã dẫn đến một thay đổi quan trọng: chính nghĩa là không chỉ là chịu đựng tội lỗi trong thế giới mà phải là cố gắng chỉnh sửa chúng.[7]. Các đạo quân thập tự chinh là tiêu biểu cho tinh thần ấy trong giai đoạn Giáo hội đang cải tổ mạnh mẽ.

- Kinh tế, chính trị: những cuộc thập tự chinh diễn ra trong thời kỳ mà dân số châu Âu phát triển mạnh mẽ và các học giả cho rằng trên khía cạnh này nó có động cơ tương tự như cuộc tấn công của người Đức vào phương Đông cũng như cuộc xâm chiếm của người Tây Ban Nha[cần dẫn nguồn]. Những cuộc thập tự chinh nhằm mục đích chiếm giữ những vùng đất mới để mở rộng sự bành trướng của phương Tây với các quốc gia Địa Trung Hải. Tuy nhiên thập tự chinh khác với những cuộc tấn công, xâm chiếm của người Đức và người Tây Ban Nha ở chỗ nó chủ yếu dành cho tầng lớp hiệp sĩ và nông dân du cư ở Palestine.

- Xã hội: tầng lớp hiệp sĩ đặc biệt nhạy cảm với sự tăng trưởng nhanh chóng của dân số châu Âu trong giai đoạn này. Họ được đào tạo, huấn luyện để tiến hành chiến tranh và trong bối cảnh dân số phát triển mạnh mẽ, những cuộc xung đột để giành đất đai đã xảy ra. Giáo hoàng Urban II đã nói với các hiệp sĩ của nước Pháp như sau: "Đất đai mà các bạn cư ngụ thì quá hẹp đối với một dân số lớn; nó cũng không thừa của cải; và nó khó lòng cung cấp đủ thực phẩm cho những người trồng trọt trên nó. Đây là lý do vì sao các bạn phải tàn sát và tàn phá lẫn nhau."[7] Như vậy, họ được khuyến khích đi viễn chinh để giành đất và trên góc độ nào đó các cuộc thập tự chinh là phương tiện bạo lực nhằm rút bạo lực ra khỏi đời sống thời Trung Cổ.[8] cũng như đem lại lợi ích kép như lời Thánh Bernard thành Clairvaux đã nói: "Sự ra đi của họ làm cho dân chúng hạnh phúc, và sự đến của họ làm phấn khởi những người đang thúc giục họ giúp đỡ. Họ giúp cả hai nhóm, không những bảo vệ nhóm này mà còn không áp bức nhóm kia.".[8]

Các cuộc Thập tự chinh

Về danh sách các cuộc thập tự chinh, chưa có sự thống nhất cao trên thế giới, danh sách này có thể lên đến 9 cuộc tùy quan điểm.

Thập tự chinh thứ nhất (1095 - 1099)

Tháng 9 năm 1095, Giáo hoàng Urban II đã có một bài thuyết giảng tại Clermont, miền nam nước Pháp kêu gọi giới quý tộc đảm nhiệm cuộc viễn chinh vào Đất Thánh. Lời kêu gọi này đã gây tác động đến mọi tầng lớp trong xã hội phương Tây và dẫn đến một cuộc thập tự chinh mang tính đại chúng với sự tham gia đông đảo của nông dân và người nghèo ở miền bắc Pháp và châu thổ sông Rhine cùng với một số hiệp sĩ và tu sỹ vào tháng 2 năm 1096, được lãnh đạo bởi một thầy tu ẩn dật người Pháp tên là Piere l'Ermite. Đội quân đông đảo nhưng trang bị thô sơ và không được tổ chức tốt này tấn công người Do Thái, từ Cologne (Đức) vượt qua Bulgaria, Hungary rồi kéo đến Constantinople. Sau khi được hoàng đế Alexios I của Byzantine đưa qua eo Bosphorus, họ nhanh chóng bị quân đội Thổ Nhĩ Kỳ đánh tan.

Ngay sau đó, một đội quân thực sự được tổ chức tốt do giới quý tộc lãnh đạo đã lên đường tiến hành cuộc thập tự chinh chính thức lần thứ nhất. Những chỉ huy gồm có: Robert xứ Normandy (con trai của William the Conqueror); Godfrey xứ Bouillon cùng hai anh trai là Baldwin xứ Boulogne và Robert xứ Flanders; Raymon IV xứ Toulouse; Bohemond I xứ Antioch, Tancred xứ Taranto,... Họ dẫn đầu 4 đạo quân theo nhiều hành trình đường bộ và đường biển đến Constantinople năm 1096 và 1097 để từ đó tấn công nhà Seljuk ở Rum. Cuối tháng 4 năm 1097, đội quân thập tự chinh tiến vào lãnh thổ của người Seljuk và giành được thắng lợi đầu tiên trong trận Dorylaeum[9] ngày 1 tháng 7 năm 1097. Chiến thắng có tính chất bước ngoặt của thập tự quân là việc đánh chiếm thành phố cảng Antioch[10] và đã giành được thắng lợi sau cuộc vây hãm kéo dài 8 tháng, mở thông đường tiến về Jerusalem. Ngày 7 tháng 6 năm 1099, Thập tự quân tới Jerusalem và bắt đầu vây hãm thành phố. Ngày 15 tháng 7 năm 1099, thập tự quân đột kích chiếm Jerusalem và tàn sát các tín đồ Hồi giáo, Do Thái giáo cũng như cả Chính thống giáo Đông phương[11]. Trong khi đoàn quân chủ yếu tiến đến Antiochia và Jerusalem thì Baldwin xứ Boulogne tách đội quân của mình ra để chiếm Edessa[12], nơi ông thiết lập Công quốc thập tự quân đầu tiên ở phương Đông. Sau đó với sự giúp đỡ của hạm đội của Venice và Genoa, Thập tự quân chiếm được toàn bộ bờ Đông Địa Trung Hải và thiết lập bá quốc Tripoli và một số tiểu quốc khác.

Kết quả của Thập tự chinh thứ nhất là đã lập ra một loạt những Công quốc Thập tự quân: Edessa, Antioch, Tripoli... và đặc biệt là Jerusalem trải rộng trên khắp vùng Cận Đông.

Thập tự chinh thứ hai (1147 - 1149)

Năm 1144, việc quân Hồi giáo tái chiếm Edessa và uy hiếp Jerusalem đã dẫn đến cuộc thập tự chinh thứ hai do Bernard thành Clairvaux tích cực phát động. Đoàn thập tự chinh gồm hai đội quân, một do vua Louis VII của Pháp, một do vua Konrad III (Hohenstaufen) của Đức chỉ huy lên đường chiếm Damascus (Syria) để tạo tiền đồn phòng thủ tốt hơn cho Jerusalem. Cuộc đột chiếm Damascus thất bại, thành phố này rơi vào tay vua Nur ad-Din Zangi, vị tiểu vương Hồi giáo đã dẫn quân đến cứu viện theo đề nghị của Damascus. Đội quân thập tự chinh phải rút về nước mà không giành được một thành quả nào ngoại trừ việc Thập tự quân Bắc Âu dừng lại ở Lisboa và cùng với người Bồ Đào Nha chiếm lại thành phố này từ người Hồi giáo.

Thập tự chinh thứ ba (1189 - 1192)

Sau khi Saladin chiếm được Ai Cập, trở thành Sultan ở đây và thống nhất các tín đồ Hồi giáo, Syria bị đe dọa nghiêm trọng, lãnh thổ của người Kitô giáo có thể bị xâm lấn bất cứ lúc nào. Năm 1187, Saladin đánh bại quân Thập tự và chiếm lại Jerusalem nên nguy cơ công quốc thập tự quân này bị xóa sổ đã hiện hữu. Trước tình hình đó, hoàng đế Friedrich I Barbarossa của đế quốc La Mã thần thánh, vua Philippe II Auguste của Pháp cùng vua Richard I Sư tử tâm của Anh đồng loạt tiến quân về phương Đông, tiến hành cuộc Thập tự chinh thứ ba. Ngày 10 tháng 6 năm 1190, Friedrich I Barbarossa chết đuối khi đang vượt sông Saleph (nay là sông Goksu) ở xứ Tiểu Á, Thổ Nhĩ Kỳ và hầu hết quân đội của ông quay trở về nước. Đội quân của Richard Sư tử tâm và Philippe II Auguste đã vây hãm và chiếm được Acre[13], đây là thắng lợi quan trọng nhất của cuộc thập tự chinh này, nhưng do mâu thuẫn vốn có giữa 2 vương quốc nên Philippe II Auguste bỏ về nước để thực hiện các kế hoạch thiết thân hơn ở Tây Âu. Mặc dù vậy, thập tự chinh thứ ba kết thúc trong bế tắc, Richard phải ký hòa ước với Saladin vào ngày 2 tháng 9 năm 1192, theo đó lãnh thổ của công quốc Jerusalem vẫn nằm trong một phạm vi hẹp từ Acre đến Jaffa và việc người Kitô giáo hành hương được quyền viếng thăm Jerusalem trong 3 năm là kết quả của cuộc viễn chinh tốn kém này. Trên đường về nước năm 1192, con tàu của Richard Sư tử tâm bị hỏng ở Aquileia (Ý), ngay trước Giáng Sinh năm ấy, ông bị Leopold V (Công tước Áo) bắt giữ rồi trao cho hoàng đế Heinrich VI (Đế quốc La Mã thần thánh). Richard Sư tử tâm bị cầm tù cho đến 4 tháng 2 năm 1194 mới được giải phóng sau khi đã trả tiền chuộc.

Thập tự chinh thứ tư (1202 - 1204)

Cuộc Thập tự chinh thứ tư bắt đầu năm 1202 do Giáo hoàng Innocent III phát động với mục tiêu chiếm Ai Cập để từ đó tấn công Jerusalem. Thế nhưng do thiếu nguồn lực tài chính nên những người chỉ huy thập tự quân đã thỏa thuận với Venezia nhằm có được phương tiện và hậu cần đảm bảo cho cuộc hành quân sang Ai Cập, để đổi lại, người Venezia sẽ nhận một nửa đất chiếm được và Thập tự quân phải trả 85000 đồng mác bằng bạc [14]. Sau đó, Venezia đề nghị đội quân thập tự chinh đánh chiếm Zara, địch thủ thương nghiệp của Venezia [15], một thành phố cũng của người Kitô giáo. Bởi còn thiếu 34000 mác, thập tự quân đã tấn công và đánh chiếm Zara vào tháng 11 năm 1202. Kế tiếp, người Venezia lại thuyết phục thập tự quân tấn công Constantinople, thủ đô của Đế quốc Byzantine theo Chính thống giáo Đông phương. Thành phố vốn đang bị chia rẽ bởi mối bất hòa giữa các phe phái này nhanh chóng thất thủ ngày 12 tháng 4 năm 1204. Mặc dù Giáo hoàng Innocent III cố gắng ngăn chặn các đạo quân thập tự, song chúng cũng cướp bóc và đốt cháy hết một phần thành phố[16]. Sau đó người Venezia và Thập tự quân phân chia đế quốc Byzantine thành các công quốc và thống trị cho đến năm 1261. Cuộc Thập tự chinh chấm dứt mà Thập tự quân không tiếp tục tiến về Đất Thánh.

Thập tự chinh thứ năm (1217 - 1219)

Thập tự chinh thứ năm do Giáo hoàng Honorius III tổ chức, Thập tự quân năm 1217 gồm các đạo quân do Leopold VI (Công tước Áo) và András II của Hungary dẫn đầu, đến năm 1218, quân đội của Oliver thành Cologne và một đội quân hỗn hợp của vua Hà Lan Willem I cũng tham gia. Mục tiêu của Thập tự quân lần này là tấn công Ai Cập. Năm 1218, John thành Brienne, vua Jerusalem bị thay thế. Năm 1219, Thập tư quân công chiếm Damietta[17] và Giáo hoàng cử đại diện là Pelagius[18] thống lĩnh cuộc Thập tự chinh. Người Hồi giáo đã đề nghị đổi quyền kiểm soát giữa Damietta và Jerusalem nhưng Pelagius từ chối. Năm 1219, Thập tự quân định tấn công Cairo nhưng không vượt qua được sông Nin đang trong mùa nước lũ và buộc phải rút lui do hậu cần không đảm bảo. Trên đường rút lui, những cuộc tấn công vào ban đêm của quân đội Hồi giáo đã gây nhiều thiệt hại cho Thập tự quân và Damietta bị tái chiếm.

Thập tự chinh thứ sáu (1228 - 1229)[19]

Đoàn quân do hoàng đế Friedrich II (Đế quốc La Mã thần thánh) đứng đầu tiến hành Thập tự chinh thứ sáu năm 1228 nhưng nhanh chóng quay trở về và Friedrich II đã bị Giáo hoàng rút phép thông công. Sau đó Friedrich II quay sang đàm phán, năm 1229 ông đạt được với người Hồi giáo một hiệp ước hòa bình trong mười năm, khôi phục lại quyền kiểm soát Jerusalem, Nazareth và Bethlehem cùng với một hành lang từ Jerusalem ra biển cho những người Kitô giáo. Trước sự chống đối của các giáo trưởng ở Jerusalem, Friedrich II đã tự phong mình làm vua ở đây năm 1229. Năm 1244, Jerusalem thất thủ trước sự tấn công ồ ạt của lính đánh thuê Hồi giáo và người Kitô giáo chỉ trở lại kiểm soát được thành phố này vào năm 1917.

Thập tự chinh thứ bảy (1248 - 1254)

Sau khi Jerusalem bị chiếm, vua Pháp Louis IX (Thánh Louis) đã chuẩn bị một cuộc Thập tự chinh vào năm 1247, mục tiêu lần này vẫn là Ai Cập. Mặc dù đội quân không được tổ chức tốt, năm 1248, ông vẫn chiếm được Damietta một cách dễ dàng và tiến quân về Cairo năm 1249. Tuy nhiên, Thập tự quân nhanh chóng bị quân Hồi giáo của Baybars I và Emir Fakr ed-Din đánh bại trong trận Mansoura[20] ngày 8 tháng 2 năm 1250, Damietta lại rơi vào tay người Hồi giáo. Vua Louis IX của Pháp bị bắt làm tù binh và được thả sau khi đã trả tiền chuộc.

Thập tự chinh thứ tám (1270)

Các sự kiện Jaffa và Antioch bị người Hồi giáo chiếm lại đã dẫn đến cuộc Thập tự chinh do Vua Louis IX tiến hành. Cuộc viễn chinh lần này nhằm đến Tunisia, Thập tự quân tấn công Tunis nhưng ngày 25 tháng 8 năm 1270, Louis IX chết ở gần Tunis vì bệnh dịch hạch. Sau đó đội quân của Louis IX cùng với đoàn Thập tự quân do hoàng tử Anh Edward tiếp tục tiến hành cuộc Thập tự chinh nhưng không đạt kết quả nào. Cuộc tấn công Tunis ngừng lại còn hoàng tử Edward dẫn quân tới Acre. Những hoạt động của đội quân do hoàng tử Edward chỉ huy trong những năm 1271 - 1272 có tài liệu gọi là Thập tự chinh thứ chín, có tài liệu lại ghép vào cùng với Thập tự chinh thứ tám. Trong hai năm này, hoàng tử Edward cũng không đạt được kết quả nào đáng kể cho đến khi ông đình chiến và quay trở về Anh để kế thừa ngôi báu sau cái chết của nhà vua Henry III. Đây cũng là cuộc viễn chinh cuối cùng trong thời Trung Cổ của người Kitô giáo tới miền Đất Thánh. Năm 1289, Tripoli bị người Hồi giáo chiếm và tới năm 1291, khi Acre cũng rơi vào tay họ thì giai đoạn của các cuộc Thập tự chinh thời trung cổ kết thúc.

Thập tự chinh thứ chín 1271–1272

Thập tự chinh phía Bắc (Baltic và Đức)

Các cuộc thập tự chinh khác

Ngoài những cuộc thập tự chinh tới miền Đất Thánh, một số hoạt động quân sự khác trong giai đoạn này cũng được gọi là Thập tự chinh như: chiến dịch quân sự chống lại giáo phái Albi ở vùng Languedoc, Pháp từ năm 1209 đến năm 1229; sự kiện thực hư lẫn lộn xảy ra năm 1212 khi hàng loạt trẻ em kéo tới Ý được gọi là Thập tự chinh của trẻ em; hay các hoạt động quân sự chống lại người Tarta, những cuộc hành binh đến Thụy Điển, vùng Balkan... cũng được coi là Thập tự chinh.

Các hiệp sĩ tham gia thập tự chinh

Ngay sau cuộc Thập tự chinh thứ nhất, các hiệp sĩ đã hình thành nên một tầng lớp mới, tầng lớp quân đội-tôn giáo. Những phẩm chất như sự cống hiến, kỷ luật và kinh nghiệm tu hành của họ được kết hợp vào mục đích quân sự của các cuộc thập tự chinh. Tầng lớp này cung cấp các đội bảo vệ vũ trang cho những đoàn hành hương về Đất Thánh, bảo vệ dân cư và trở nên rất cần thiết cho các vương triều phương Tây cũng như đóng vai trò quan trọng trong xã hội châu Âu thời kỳ đó.

- Hiệp sĩ dòng Đền (hay Hiệp sĩ Đền thờ; Tiếng Pháp: Ordre du Temple) do các hiệp sĩ Pháp thành lập đầu thế kỷ XII. Họ sống chung với nhau trong các khu nhà hoặc cộng đồng riêng và tôn chỉ là 3 lời thề tu sỹ: nghèo khó, thanh khiết và phục tùng. Họ tự ý thức trách nhiệm của mình trong việc bảo vệ Công quốc Jerusalem, đảm bảo sự an toàn cho các tuyến đường nối tây Âu với các Công quốc Thập tự quân. Các Hiệp sĩ Đền thờ cũng đảm nhận việc vận chuyển, bảo vệ tiền bạc rất cần thiết cho những cuộc thập tự chinh diễn ra liên tục và do vậy trở thành thể chế ngân hàng quan trọng nhất của thời đại[21]. Năm 1321, các hoạt động của Hiệp sĩ Đền thờ bị Giáo hoàng ra lệnh cấm.

- Hiệp sĩ Cứu tế Thánh Gioan hay gọi ngắn gọn là Hiệp sĩ Cứu tế (Anh ngữ:Knights Hospitaller): do các hiệp sĩ ở Jerusalem thành lập vào khoảng năm 1103. Tuy quân số không đông bằng Hiệp sĩ Đền thờ nhưng họ đã giữ vai trò quan trọng trong công cuộc bảo vệ Công quốc Jerusalem trong suốt thời gian xảy ra những cuộc Thập tự chinh. Năm 1291, sau khi thành Acre thất thủ, tổng hành dinh của Hiệp sĩ Cứu tế dời đến Cộng hòa Síp rồi sau đó đến đảo Rhodes và cuối cùng là đảo Malta. Cùng với các hiệp sĩ ở Malta, họ cai trị hòn đảo này cho đến năm 1798 khi Napoléon Bonaparte chiếm Malta trên con đường chinh phục Ai Cập. Các hiệp sĩ trở thành Giai cấp tối cao (sovereign order) ở Malta và còn tồn tại đến ngày nay như một nhóm chuyên làm các công việc bác ái.

- Hiệp sĩ Giéc-man (tiếng Đức: Deutscher Orden): được thành lập vào khoảng năm 1190 ở Acre để bảo vệ các đoàn hành hương người Đức đến Palestine. Tổng hành dinh của họ sau được dời đến Venezia, rồi Transynvania[22] năm 1211 và cuối cùng là đến Phổ năm 1299. Các Hiệp sĩ Giécman đã trở thành đội quân tiên phong của Đức mở rộng lãnh thổ về phía đông và chiếm được một vùng đất dọc theo biển Baltic. Năm 1525, trong phong trào cải cách tôn giáo ở châu Âu, Albert thành Brandenburg, một đại địa chủ theo học thuyết của Martin Luther đã nắm quyền kiểm soát ở đây và giải trừ quyền hành của tầng lớp Hiệp sĩ Giécman.

Dấu ấn của Thập tự chinh

Hai lực lượng chính đối đầu nhau trong những cuộc thập tự chinh là những người Kitô giáo và Hồi giáo có quan điểm đánh giá rất khác nhau về những cuộc Thập tự chinh. Đối với phương Tây, Thập tự chinh là những cuộc viễn chinh mạo hiểm nhưng anh hùng, những người tham gia thập tự chinh, dù rất nhiều trong số họ đã bỏ mình nơi chiến địa được xem là tiêu biểu cho sự dũng cảm và tinh thần hiệp sĩ. Richard Sư tử tâm được xem là vị vua đắc thủ tất cả những đức tính của một hiệp sĩ kiểu mẫu - gan dạ, thiện chiến, phong độ uy nghi, ngay cả sự nhạy bén để soạn những bài ca trữ tình của giới ca sĩ hát rong.[23]. Louis IX, vị vua đã băng hà trong cuộc Thập tự chinh ở Tunisia, với đức tính ngoan đạo, khổ hạnh cũng như công lý mà ông đem lại cho nền quân chủ Pháp thậm chí trong suốt cuộc đời mình, vua Louis đã được xem là bậc thánh.[24]. Cao lớn, đẹp trai, lịch thiệp và quả cảm, vua Friedrich I Barbarossa, cũng giống như vị vua trước đó là Charlemagne, đã giành được vị trí lâu dài trong ký ức và huyền thoại của thần dân.[25]. Godfrey xứ Bouillon, với chiến công cùng với một nhóm hiệp sĩ của mình là những người đầu tiên vượt qua tường thành để xâm nhập Jerusalem và chiếm lại Đất Thánh trong cuộc vây hãm ở Thập tự chinh thứ nhất đã trở thành huyền thoại. Ông được người châu Âu thời ấy xếp vào một trong số Chín biểu tượng của tinh thần hiệp sĩ trong mọi thời đại, được ca ngợi trong những bản trường ca, một thể loại vốn phổ biến ở Pháp thời trung cổ. Cuộc tấn công Antioch cũng là chủ đề của bản Trường ca Antioch dài hơn 9.000 câu thơ. Những bài hát của ca sĩ hát rong ở khắp châu Âu ca ngợi những thủ lĩnh, những hiệp sĩ thập tự chinh và những mối tình lãng mạn của họ.

Dấu ấn lịch sử của Thập tự chinh trong thế giới Hồi giáo không đậm nét bằng ở phương Tây mặc dù những vị vua Hồi giáo chống lại người Kitô giáo như Nur ad-Din,...đặc biệt là Saladin cũng rất được ngưỡng mộ và kính trọng. Đối với người Hồi giáo, Thập tự chinh là những sự kiện đầy tàn bạo và dã man và những cuộc chiến đấu của họ chống lại Thập tự quân được gọi là Thánh chiến.

Ảnh hưởng của Thập tự chinh

Mặc dù các cuộc Thập tự chinh không tạo ra sự hiện diện thường xuyên và vững chắc của phương Tây tại Tiểu Á nhưng sự tiếp xúc giữa văn hóa phương Đông và phương Tây đã có ảnh hưởng mạnh mẽ đến hai nền văn hóa này.

- Kỹ thuật quân sự: sau những cuộc Thập tự chinh đầu tiên, Thập tự quân đã phải tiến hành các chiến dịch phòng thủ quy mô lớn ở những tiền đồn xa xôi và điều này khiến cho kỹ thuật phòng vệ, đặc biệt là kỹ thuật xây dựng lâu đài phát triển. Các lâu đài có thiết kế công sự tháp treo để thuận lợi cho việc bắn vũ khí, ném gỗ, đá, dầu... vào những người tấn công; lối vào lâu đài được bố trí các góc, tường ngăn không cho đối phương công phá trực tiếp. Các lâu đài Hồi giáo cũng có bước phát triển tương tự. Cùng với kỹ thuật phòng thủ, các phương tiện công thành như máy bắn đá, máy phá thành bằng những khúc gỗ lớn...trở nên tinh vi và hiệu quả hơn; các kỹ thuật đào đất, đặt chất nổ...cũng có bước phát triển.

- Kinh tế: mặc dù không có số liệu thống kê tin cậy về thu nhập cũng như phí tổn của các cuộc Thập tự chinh nhưng chắc chắn rằng chúng rất tốn kém, đặc biệt là đối với phương Tây do họ phải tiến hành viễn chinh. Chiến tranh đã làm cạn kiệt dần nguồn lực của phương Tây dẫn đến phải áp dụng thuế ở mức độ cao. Để tài trợ cho Thập tự chinh thứ ba, năm 1188, với sự cho phép của Giáo hoàng, các vương công đã đánh thuế trực thu 10% trên thu nhập của tất cả tu sỹ và người dân có thu nhập gọi là Thuế thập phân Saladin. Thuế cũng kéo theo sự phát triển của các kỹ thuật quản lý, thu thuế, chuyển tiền...Mặt khác, Thập tự chinh kích thích thương mại giữa phương Đông và phương Tây: các sản phẩm như đường, gia vị,... từ phương Đông được buôn bán rất mạnh; các mặt hàng xa xỉ như vải lụa...cũng được phát triển sản xuất ngay tại châu Âu.

- Các cuộc thăm dò: Thập tự chinh đã kích thích những cuộc thăm dò của người phương Tây đến những nền văn hóa phương Đông. Khởi phát là các công quốc có Thập tự quân, các tu sỹ rồi đến thương gia; họ đã thâm nhập sâu vào lục địa châu Á và đầu thế kỷ XIII đã đến Trung Hoa. Những chuyến đi của họ, đặc biệt là của Marco Polo đã cung cấp cho châu Âu nguồn thông tin đa dạng và quý báu về Đông Á, tạo tiền đề cho những nhà hàng hải tìm kiếm các lộ trình mới để buôn bán với Trung Hoa vào cuối thế kỷ XV và thế kỷ XVI. Khát vọng thăm dò, chiếm đoạt các nền văn hóa khác, và mở rộng Kitô giáo là một phần mà các cuộc Thập tự chinh đã truyền cảm hứng cho chủ nghĩa đế quốc sau này.[26].

- Chính trị:

- Văn hóa:

Xin hãy đóng góp cho bài viết này bằng cách phát triển nó. Nếu bài viết đã được phát triển, hãy gỡ bản mẫu này. Thông tin thêm có thể được tìm thấy tại trang thảo luận. |

Xem thêm

Chú thích

- ^ a b Riley-Smith, Jonathan. The Oxford History of the Crusades New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-19-285364-3.

- ^ Riley-Smith, Jonathan. The First Crusaders, 1095–1131 Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-521-64603-0.

- ^ Như lãnh thổ Hồi giáo ở Al-Andalus, Ifriqiya, và Ai Cập, cũng như ở Đông Âu

- ^ e.g. the Albigensian Crusade, the Aragonese Crusade, the Reconquista, and the Northern Crusades.

- ^ Halsall, Paul (1997). “Philip de Novare: Les Gestes des Ciprois, The Crusade of Frederick II, 1228–29”. Medieval Sourcebook. Fordham University. Truy cập ngày 8 tháng 2 năm 2008.—"Gregory IX had in fact excommunicated Frederick before he left Sicily the second time"

- ^ The Gospel in All Lands By Methodist Episcopal Church Missionary Society, Missionary Society, Methodist Episcopal Church, pg. 262

- ^ a b Mortimer Chambers,...; Tr. 314.

- ^ a b Mortimer Chambers,...; Tr. 315.

- ^ Dorylaeum: một thành phố cổ thuộc Tiểu Á, phế tích của nó ở gần thành phố Eskisehir ngày nay.

- ^ Antioch: một thành phố cổ ở địa điểm nay là thành phố Antakya, Thổ Nhĩ Kỳ.

- ^ Mortimer Chambers,...; Tr. 317.

- ^ Edessa: thành phố cổ phía nam Thổ Nhĩ Kỳ, ở vị trí nay là Sanliurfa (Urfa)

- ^ Acre: một thành phố cảng nằm ven vịnh Haifa, Israel.

- ^ Dịch giả: Nguyễn Gia Phu, Nguyễn Văn Ánh, Đỗ Đình Hằng, Trần Văn La. Lịch sử thế giới trung đại. Trang 54. Nhà xuất bản giáo dục.2006.

- ^ Zara: một thành phố thuộc Croatia ngày nay, nằm ven biển Adriatic.

- ^ Mortimer Chambers,..; Tr. 321.

- ^ Damietta: thành phố cảng ở Ai Cập, cách Cairo 200 km về phía bắc.

- ^ Pelagus: tên thật là Pelagio Galvani (? - 1230), Hồng y người Tây Ban Nha.

- ^ Có tài liệu không coi đây là một cuộc Thập tự chinh riêng rẽ mà ghép nó vào cuộc Thập tự chinh thứ năm

- ^ Mansoura hay El Mansurah: một thành phố trong vùng châu thổ sông Nin, cách Cairo 120 km về phía đông bắc.

- ^ Mortimer Chambers,...; Tr. 321.

- ^ Transynvania: một vùng đất trong lịch sử bao gồm lãnh thổ miền Trung Tây Romania ngày nay.

- ^ Mortimer Chambers,...; Tr.348.

- ^ Mortimer Chambers,...; Tr.354.

- ^ Mortimer Chambers,...; Tr.357.

- ^ Mortimer Chambers,...; Tr. 323.

Tham khảo

- Mortinmer Chambers, Barbara Hanawalt, David Herlihy, Theodore Rabb K., Isser Woloch, Raymond Grew - Lịch sử văn minh phương Tây, Nhà xuất bản Văn hóa - Thông tin (2004)

- Atwood, Christopher P. (2004). The Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. Facts on File, Inc. ISBN 0-8160-4671-9.

- Erdmann, Carl, The Origin of the Idea of Crusade, trans. M. W. Baldwin & Walter Goffart, in English (Princeton, 1977). Original work in German, Die Enstehung des Kreuzzugsgedanken, Forschungen zur Kirchen- und Geistesgeschichte 6 (Stuttgart, 1935).

- The Encyclopedia of World History. 2001 Lưu trữ 2007-12-17 tại Wayback Machine

- The Crusades Lưu trữ 2007-10-26 tại Wayback Machine

Xem thêm

Liên kết ngoài

| Wikimedia Commons có thêm hình ảnh và phương tiện truyền tải về Thập tự chinh. |

- Biên niên về các cuộc Thập tự chinh (tiếng Anh)

- E.L. Skip Knox, The Crusades Lưu trữ 2010-10-10 tại Wayback Machine, a virtual college course through Boise State University.

- Crusades: A Guide to Online Resources Lưu trữ 2013-12-06 tại Wayback Machine, Paul Crawford, 1999.

- The Society for the Study of the Crusades and the Latin East—an international organization of professional Crusade scholars

- De Re Militari: The Society for Medieval Military History—contains articles and primary sources related to the Crusades

- Resources > Medieval Jewish History > The Crusades Lưu trữ 2007-10-11 tại Wayback Machine The Jewish History Resource Center - Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- The Crusades Encyclopedia - articles, primary and secondary sources, and bibliographies

- An Islamic View of the Battlefield an article that provides indepth analysis of the theological basis of human wars

- A History of the Crusades

- A History Of The Crusades by Terry Jones

- The Crusades Wiki

llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll

llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll

Exorcism

Exorcism (from Greek ἐξορκισμός, exorkismós, "binding by oath") is the religious or spiritual practice of evicting demons, jinns, or other spiritual entities from a person, or an area, that is believed to be possessed.[1] Depending on the spiritual beliefs of the exorcist, this may be done by causing the entity to swear an oath, performing an elaborate ritual, or simply by commanding it to depart in the name of a higher power. The practice is ancient and part of the belief system of many cultures and religions.

Requested and performed exorcism began to decline in the United States by the 18th century and occurred rarely until the latter half of the 20th century when the public saw a sharp rise due to the media attention exorcisms were getting. There was "a 50% increase in the number of exorcisms performed between the early 1960s and the mid-1970s".[2]

Buddhism

The practice of reciting or listening to the Paritta began very early in the history of Buddhism, it is a Buddhist practice of reciting certain verses and scriptures from Pali Canon in order to ward off misfortune or danger. The belief in the effective spiritual power to heal, or protect, of the Sacca-kiriyā, or asseveration of something quite true is an aspect of the work ascribed to the paritta.[3] Several scriptures in the Paritta like Metta Sutta, Dhajagga Sutta, Ratana Sutta can be recite for exorcism purpose, and Āṭānāṭiya Sutta is particularly effective for exorcism purpose. [4]

Sinhalese Buddhism

In Sri Lanka, Sinhala Buddhists invoke the protection of the Buddha as well as the deity Suniyam to control and disperse dangerous supernatural forces in a ritual known as the yaktovil.[5]

Tibetan Buddhism

The ritual of the Exorcising-Ghost day is part of Tibetan tradition. The Tibetan religious ceremony 'Gutor' ༼དགུ་གཏོར་༽, literally offering of the 29th, is held on the 29th of the 12th Tibetan month, with its focus on driving out all negativity, including evil spirits and misfortunes of the past year, and starting the new year in a peaceful and auspicious way.

The temples and monasteries throughout Tibet hold grand religious dance ceremonies, with the largest at Potala Palace in Lhasa. Families clean their houses on this day, decorate the rooms and eat a special noodle soup called 'Guthuk'. ༼དགུ་ཐུག་༽ In the evening, the people carry torches, calling out the words of exorcism.[6]

Christianity

In Christianity, exorcism is the practice of casting out or getting rid of demons. In Christian practice the person performing the exorcism, known as an exorcist, is often a member of the Christian Church, or an individual thought to be graced with special powers or skills. The exorcist may use prayers and religious material, such as set formulas, gestures, symbols, icons, amulets, etc. The exorcist often invokes God, Jesus or several different angels and archangels to intervene with the exorcism. Protestant Christian exorcists most commonly believe the authority given to them by the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (the Trinity) is the sole source of their ability to cast out demons.[7]

In general, people considered to be possessed are not regarded as evil in themselves, nor wholly responsible for their actions, because possession is considered to be unwilling manipulation by a demon resulting in harm to self or others. Therefore, practitioners regard exorcism as more of a cure than a punishment. The mainstream rituals usually take this into account, making sure that there is no violence to the possessed, only that they be tied down if there is potential for violence.[8] However, there are Biblical verses, like John 13:27, that implicitly convey that demonic possession can be voluntary, as exemplified in individuals like Judas Iscariot, who willingly submitted to the Devil.[9]

Catholicism

In Catholicism, exorcisms are performed in the name of Jesus Christ.[10] A distinction is made between a formal, or solemn, exorcism, which can only be conducted by a priest during a baptism or with the permission of a bishop, and "prayers of deliverance", which can be said by anyone.

The Catholic rite for a formal exorcism, called a "Major Exorcism", is given in Section 11 of the Rituale Romanum.[11][12] The Ritual lists guidelines for conducting an exorcism, and for determining when a formal exorcism is required.[13] Priests are instructed to carefully determine that the nature of the affliction is not actually a psychological or physical illness before proceeding.[10]

In Catholic practice, the person performing the exorcism, known as an exorcist, is an ordained priest. The exorcist recites prayers according to the rubrics of the rite, and may make use of religious materials such as icons, sacramentals, and relics. The exorcist invokes God—specifically the Name of Jesus Christ—as well as members of the Church Triumphant and the Archangel Michael to intervene with the exorcism. According to Catholic understanding, several weekly exorcisms over many years are sometimes required to expel a deeply entrenched demon.[13][14]

Saint Michael's Prayer against Satan and the Rebellious Angels, attributed to Pope Leo X, is considered the strongest prayer of the Catholic Church against cases of diabolic possession.[15] The Holy Rosary also has an exorcistic and intercessory power.[citation needed]

Eastern Orthodoxy

The Eastern Orthodox Church has a rich and complex tradition of exorcism.[16] The practice is traced to biblical accounts of Jesus expelling demons and exhorting his apostles to "cast out devils".[17] The church views demonic possession as the devil's primary means of enslaving humanity and rebelling against God. Orthodox Christians believe objects, as well as individuals, can be possessed.[18]

As in other Christian churches, Orthodox exorcists expel demons by invoking God through the name of Jesus Christ.[19] Unlike the Roman Catholic Church, which has a specially trained unit of exorcists, all priests of the Orthodox Church are trained and equipped to perform exorcisms, particularly for the sacrament of baptism. Like their Catholic counterparts, Orthodox priests learn to distinguish demonic possession from mental illness, namely by observing whether the subject reacts negatively to holy relics or places.[18] All Orthodox liturgical books include prayers of exorcism, namely by Saint Basil and Saint John Chrysostom.

Orthodox theology takes a uniquely expansive view of exorcism, believing every Christian undertakes exorcism through their struggle against sin and evil:

[T]he whole Church, past, present and future, has the task of an exorcist to banish sin, evil, injustice, spiritual death, the devil from the life of humanity ... Both healing and exorcising are ministered through prayers, which spring from faith in God and from love for man ... All the prayers of healing and exorcism, composed by the Fathers of the Church and in use since the third century, begin with the solemn declaration: In Thy Name, O Lord.[20]

Additionally, many Orthodox Christians subscribe to the superstition of Vaskania, or the "evil eye", in which those harboring intense jealousy and envy towards others can bring harm to them (akin to a curse) and are, in effect, demonically possessed by these negative emotions.[21] This belief is most likely rooted in pre-Christian paganism, and although the church rejects the notion that the evil eye can have such power, it does recognize the phenomenon as morally and spiritual undesirable and thus a target for exorcism.[22]

Lutheran Churches

From the 16th century onward, Lutheran pastoral handbooks describe the primary symptoms of demonic possession to be knowledge of secret things, knowledge of languages one has never learned, and supernatural strength.[23] Before conducting a major exorcism, Lutheran liturgical texts state that a physician be consulted in order to rule out any medical or psychiatric illness.[23] The rite of exorcism centers chiefly around driving out demons "with prayers and contempt" and includes the Apostles' Creed and the Lord's Prayer.[23]

Baptismal liturgies in Lutheran Churches include a minor exorcism.[24][25]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

While a very rare practice in the Church, there are two methods for performing an exorcism. The first is by anointing with consecrated oil and laying on of hands followed by a blessing on a specific person and commanding the spirit to leave.[26] The second and most common method is done by "raising the hand to the square" and then "commanding the spirit away in the name of Jesus Christ and with the power or authority of the Melchizedek priesthood".[26][27] Exorcisms can only be performed by someone holding the Melchizedek priesthood, the higher of the two priesthoods of the Church,[26] and can be performed by anyone holding that priesthood, however they are generally performed by bishops, missionaries, mission presidents, or stake presidents.[26] Exorcisms are not recorded by the Church and therefore the number of exorcisms performed in the religion are unknown.

Demonic possession is rarely talked about in the church. Demonic possession has been talked about twice by Joseph Smith, the founder of the faith. The first time refers to his experience during the First Vision[26] and he recorded the following in his "1831 account of the First Vision":

I kneeled down and began to offer up the desires of my heart to God, I had scarcely done so, when immediately I was seized upon by some power which entirely overcame me and had such astonishing influence over me as to bind my tongue so that I could not speak. Thick darkness gathered around me and it seemed to me for a time as if I were doomed to sudden destruction. But exerting all my powers to call upon God to deliver me out of the power of this enemy which had seized upon me, and at the very moment when I was ready to sink into despair and abandon myself to destruction, not to an imaginary ruin but to the power of some actual being from the unseen world who had such a marvelous power as I had never before felt in any being, just at this moment of great alarm I saw a pillar of light exactly over my head above the brightness of the sun, which descended gradually until it fell upon me.[28]

His second experience comes from a journal entry in which he talks about the time he performed an exorcism on a friend.[29][26][27]

Hinduism

In many Hindu traditions, people can be possessed by bhuts or prets, restless and often malignant beings roughly analogous to ghosts,[31] and to a lesser extent, demons.[32]

Of four Vedas, or holy books, of Hinduism, the Atharva Veda is most focused on knowledge such as exorcism,[33] magic, and alchemy.[34] The basic means of exorcism are the mantra (a sacred utterance of certain phonemes or phrases that is often connected to a particular deity) and the yajna (a sacrifice, offering, or ritual done before a sacred fire). These are performed in accordance with Vedic traditions as well as the Tantra, the later esoteric teachings and practices within Hinduism.

Within the dominant Hindu sect of Vaishnava, which reveres Vishnu as the supreme being, exorcisms are performed by reciting the names of Narasimha, a fierce avatar of Vishnu that seeks to destroy evil and restore Dharma, or by reading the Bhagavata Purana, a highly revered text that tells the story of good vanquishing evil. Another resource for exorcisms is the Garuda Purana, a vast corpus of literature mostly centered on Vishnu, deals heavily with topics related to death, disease, good versus evil, and spiritual health.[35]

The devotional hymn known as Hanuman Chalisab advises conducting exorcisms by praying to Lord Hanuman, the most devoted follower of Rama, a major Hindu deity. Among some devotees, merely uttering Hanuman's name terrifies evil spirits into leaving the possessed. Some Hindu temples, most notably the Mehandipur Balaji Temple in Rajasthan, host exorcism rituals that invoke incarnations of Hanuman.[36]

Islam

Terms for exorcism practices include ṭard (or dafʿ) al-shayṭān/al-jinn (expulsion of the demon/the spirit), ʿilāj (treatment), and ibrāʾ al-maṣrūʿ (curing the possessed), but also ruḳya (enchantment)[37] is used to exorcise various spirits.[38]

Islamic exorcisms might consist of the treated person lying down, while a sheikh places a hand on a patient’s head and recites verses from the Quran, but this is not mandatory.[39] The drinking or sprinkling of holy water (water from the Zamzam Well) may also take place along with applying of clean, non-alcohol-based perfumes, called ittar.[40]

Specific verses from the Quran are recited, which glorify God (e.g. The Throne Verse (Arabic: آية الكرسي Ayatul Kursi)), and invoke God's help. In some cases, the adhan (call for daily prayers) is also read, as this has the effect of repelling non-angelic unseen beings or the jinn.[41]

The Islamic prophet Muhammad taught his followers to read the last three suras from the Quran, Surat al-Ikhlas (The Fidelity), Surat al-Falaq (The Dawn) and Surat an-Nas (Mankind). Hadiths reporting Muhammad, but also Jesus, performing exorcism rites serve as example and permissibility for exorcism rites.[42]

Judaism

Josephus reports exorcisms performed by administering poisonous root extracts and others by making sacrifices.[43]

In more recent times, Rabbi Yehuda Fetaya (1859–1942) authored the book Minchat Yahuda, which deals extensively with exorcism, his experience with possessed people, and other subjects of Jewish thought. The book is written in Hebrew and was translated into English.

The Jewish exorcism ritual is performed by a rabbi who has mastered practical Kabbalah. Also present is a minyan (a group of ten adult males), who gather in a circle around the possessed person. The group recites Psalm 91 three times, and then the rabbi blows a shofar (a ram's horn).[44]

The shofar is blown in a certain way, with various notes and tones, in effect to "shatter the body" so that the possessing force will be shaken loose. After it has been shaken loose, the rabbi begins to communicate with it and ask it questions such as why it is possessing the body of the possessed. The minyan may pray for it and perform a ceremony for it in order to enable it to feel safe, and so that it can leave the person's body.[44]

Taoism/Chinese folk religion

In Taoism, exorcisms are performed because an individual has been possessed by an evil spirit for one of two reasons. The individual has disturbed a ghost, regardless of intent, and the ghost now seeks revenge. An alive person could also be jealous and uses black magic as revenge thereby conjuring a ghost to possess someone.[45] The Fashi, who are both Chinese ritual specialists and Taoist priests, are able to conduct particular rituals for exorcism.

Historically, Taoist exorcisms include usage of Fulu, chanting, physical gesture like mudras, and praying as a way to drive away the spirit.[46]

The leaders of these exorcism rituals who are tangki that invited the divine powers from the Deities and conduct a dramatic performance to call out against the demons so the village can once again have peace. The leaders strike themselves with various sharp weapons to show their invincibility to ward off the demons and also to let out their blood. This form of blood is considered to be sacred and powerful, so after the rituals, the blood is blotted with talismans and placed on the door of houses as an act of spiritual protection against evil spirits.[47]

Scientific view

Demonic possession is not a psychiatric or medical diagnosis recognized by either the DSM-5 or the ICD-10. Those who profess a belief in demonic possession have sometimes ascribed to possession the symptoms associated with physical or mental illnesses, such as hysteria, mania, psychosis, Tourette's syndrome, epilepsy, schizophrenia or dissociative identity disorder.[48][49][50][51][52][53]

Additionally, there is a form of monomania called demonomania or demonopathy in which the patient believes that they are possessed by one or more demons.[54] The illusion that exorcism works on people experiencing symptoms of possession is attributed by some to placebo effect and the power of suggestion.[55][56] Some cases suggest that supposedly possessed persons are actually narcissists or are suffering from low self-esteem and act demonically possessed in order to gain attention.[57]

Within the scientific community, the work of psychiatrist M. Scott Peck, a believer in exorcism, generated significant debate and derision. Much was made of his association with (and admiration for) the controversial Malachi Martin, a Roman Catholic priest and a former Jesuit, despite the fact that Peck consistently called Martin a liar and a manipulator.[58][59] Other criticisms leveled against Peck included claims that he had transgressed the boundaries of professional ethics by attempting to persuade his patients to accept Christianity.[58]

Exorcism and mental illness

One scholar has described psychosurgery as "Neurosurgical Exorcisms", with trepanation having been widely used to release demons from the brain.[60] Meanwhile, another scholar has equated psychotherapy with exorcism.[61]

United Kingdom

In the UK, exorcisms are increasing. They happen mainly in charismatic and Pentecostal churches, and also among communities of West African origin. Frequently, the people exorcised are mentally disturbed. Mentally ill people are sometimes told to stop their medication as the church believes prayer or exorcism is enough. If psychiatric patients do not get better after exorcism, they may believe they have failed to overcome the demon and get worse.[62]

Notable exorcisms and exorcists

- (1578) Martha Broissier was a young woman who was made infamous around the year of 1578 for her feigned demonic possession discovered through exorcism proceedings.[63]

- (1619) Mademoiselle Elizabeth de Ranfaing, who having become a widow in 1617 was later sought in marriage by a physician (afterwards burned under judicial sentence for being a practicing magician). After being rejected, he gave her potions to make her love him which occasioned strange developments in her health and proceeded to continuously give her some other forms of medicament. The maladies which she suffered were incurable by the various physicians that attended her and eventually led to a recourse of exorcisms as prescribed by several physicians that examined her case. They began to exorcise her in September, 1619. During the exorcisms, the demon that possessed her purportedly made detailed and fluid responses in varying languages including French, Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Italian and was able to know and recite the thoughts and sins of various individuals who examined her. She was further also purported to describe in detail with the use of various languages the rites and secrets of the church to experts in the languages she spoke. There was even a mention of how the demon interrupted an exorcist, who after making a mistake in his recital of an exorcism rite in Latin, corrected his speech and mocked him.[64]

- (1778) George Lukins[65]

- (1842-1844) Johann Blumhardt performed the exorcism of Gottliebin Dittus over a two-year period in Möttlingen, Germany, from 1842–1844. Pastor Blumhardt's parish subsequently experienced growth marked by confession and healing, which he attributed to the successful exorcism.[66][67]

- (1906) Clara Germana Cele was a South African school girl who claimed to be possessed.[68]

- (1947) Art expert Armando Ginesi claims Salvador Dalí received an exorcism from Italian friar Gabriele Maria Berardi while he was in France. Dalí would have created a sculpture of Christ on the cross that he would have given to the friar in thanks.[69]

- (1949) A boy identified as Robbie Mannheim[70][71] was the subject of an exorcism in 1949, which became the chief inspiration for The Exorcist, a horror novel and film written by William Peter Blatty, who heard about the case while he was a student in the class of 1950 at Georgetown University. Robbie was taken into the care of Rev. Luther Miles Schulze, the boy's Lutheran pastor, after psychiatric and medical doctors were unable to explain the disturbing events associated with the teen; the minister then referred the boy to Rev. Edward Hughes, who performed the first exorcism on the teen.[72] The subsequent exorcism was partially performed in both Cottage City, Maryland, and Bel-Nor, Missouri,[73] by Father William S. Bowdern, S.J., Father Raymond Bishop S.J. and a then Jesuit scholastic Fr. Walter Halloran, S.J.[74]

- (1974) Michael Taylor[75]

- (1975) Anneliese Michel was a Catholic woman from Germany who was said to be possessed by six or more demons and subsequently underwent a secret, ten-month-long voluntary exorcism. Two motion pictures, The Exorcism of Emily Rose and Requiem, are loosely based on Anneliese's story. The documentary movie Exorcism of Anneliese Michel[76] (in Polish, with English subtitles) features the original audio tapes from the exorcism. The two priests and her parents were convicted of negligent manslaughter for failing to call a medical doctor to address her eating disorder as she died weighing only 68 pounds.[77] The case has been labelled a misidentification of mental illness, negligence, abuse, and religious hysteria.[78]

- Bobby Jindal, former governor of Louisiana, wrote an essay in 1994 about his personal experience of performing an exorcism on an intimate friend named "Susan" while in college.[79][80]

- Mother Teresa allegedly underwent an exorcism late in life under the direction of the Archbishop of Calcutta, Henry D'Souza, after he noticed she seemed to be extremely agitated in her sleep and feared she "might be under the attack of the evil one."[81]

- (2005) Tanacu exorcism is a case in which a mentally ill Romanian nun was killed during an exorcism by priest Daniel Petre Corogeanu.

- The October 2007 mākutu lifting (ceremonial lifting of a sorcery or witchcraft curse) in the Wellington, New Zealand, suburb of Wainuiomata led to a death by drowning of a woman and the hospitalization of a teen. After a long trial, five family members were convicted and sentenced to non-custodial sentences.[82]

See also

- Deliverance ministry

- Gay exorcism

- International Association of Exorcists

- Kecak

- List of exorcists

- Of Exorcisms and Certain Supplications

- Paritta

- Phurba

- Sak Yant

- Yaktovil

- Yoruba religion

References

- "Deadly curse verdict: five found guilty". The Dominion Post. 13 June 2009. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

Works cited

- Monier-Williams, Monier (1974), Brahmanism and Hinduism: Or, Religious Thought and Life in India, as Based on the Veda and Other Sacred Books of the Hindus, Elibron Classics, Adamant Media Corporation, ISBN 978-1-4212-6531-5, retrieved 8 July 2007

Further reading

- Abraham Hartwell (1599). A True Discourse Upon the Matter of Martha Brossier of Romorantin, pretended to be possessed by a Devil. 2018. ISBN 978-1987654431.

- Augustin Calmet (1751) "Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants: of Hungary, Moravia, et al. The Complete Volumes I & II. 2016 ISBN 978-1-5331-4568-0

- Barry Beyerstein. (1995). Dissociative States: Possession and Exorcism. In Gordon Stein (ed.). The Encyclopedia of the Paranormal. Prometheus Books. pp. 544–52. ISBN 1-57392-021-5

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, nn. 391–95; 407.409.414.

- David M. Kiely and Christina McKenna. (2007). The Dark Sacrament : True Stories of Modern-Day Demon Possession and Exorcism. HarperOne. ISBN 0-06-123816-3

- Frederick M. Smith. (2006). The Self Possessed: Deity and Spirit Possession in South Asian Literature and Civilization. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-13748-6

- Josephine McCarthy. (2010). The Exorcists Handbook. Golem Media Publishers. ISBN 978-1-933993-91-1

- Gabriele Amorth. (1999). An Exorcist Tells His Story. San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

- Girolamo Menghi, Gaetano Paxia. (2002). The Devil's Scourge – Exorcism during the Italian Renaissance. Weiser Books.

- Kazuhiro Tajima-Pozo et al. (2011). "Practicing exorcism in schizophrenia". Case Reports.

- Michael W. Cuneo, American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty, Doubleday. 2001. ISBN 0-385-50176-5. Sociological account.

- Malachi Martin. (1976). Hostage to the Devil: The Possession and Exorcism of Five Living Americans. ISBN 0-06-065337-X

- M. Scott Peck. (2005). Glimpses of the Devil: A Psychiatrist's Personal Accounts of Possession, Exorcism, and Redemption.

- William Trethowan. (1976). "Exorcism: A Psychiatric Viewpoint". Journal of Medical Ethics 2: 127–37.

- Walter F. Williams. (2000). Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience: From Alien Abductions to Zone Therapy. Fitzroy Dearborn. pp. 103–04

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Exorcism. |

- "Exorcism: Facts and Fiction About Demonic Possession" by Benjamin Radford.

- "An Evening with an Exorcist," a talk given by Fr. Thomas J. Euteneuer* Catholic Exorcism – Web Site

- Bobby Jindal. BEATING A DEMON: Physical Dimensions of Spiritual Warfare. (New Oxford Review, December 1994)

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Exorcism

- Diocese of Worcester webpages on Ministry of Deliverance Anglican View

- Exorcism in the Orthodox Church

- The Catholic Prayer of Exorcism in Latin

- Exorcism by therapists called Spirit Release Therapy

Anthropological date collected by Mohr and Royal (2012), in which they surveyed nearly 200 Protestant Christian exorcists, revealed stark contrasts to traditional Catholic practices.

A brief exorcism found its way into early Lutheran baptismal services and an exorcism prayer formula is recorded in the First Prayer Book of Edward VI (1549).

This liturgy retained the minor exorcism (a formal renunciation of the devil's works and ways), which later in the sixteenth century became an issue dividing Lutherans and Calvinists.

The Reverend Luther Miles Schulze, was called in to help and took Mannheim to his home where he could study the phenomenon at close range;

A thirteen-year-old American boy named, Robert Mannheim, started using an...The Reverend Luther Miles Schulze, who was called to look into the matter,...

llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll

The Many Myths of the Term ‘Crusader’

Conceptions of the medieval Crusades tend to lump disparate movements together, ignoring the complexity and diversity of these military campaigns

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0d/ce/0dce31ef-6e4a-4708-af4b-cb848fd33dab/crusadesa.jpg)

In the middle of October, a diver off the coast of Israel resurfaced with a spectacular find: a medieval sword encrusted with marine life but otherwise in remarkable condition. He immediately turned the weapon over to the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA). Two days later, before the artifact had been cleaned or definitively dated, the government agency released a statement in which IAA inspector Nir Distelfeld said, “The sword, which has been preserved in perfect condition, is a beautiful and rare find and evidently belonged to a Crusader knight.” The news rocketed around the world, with dozens of outlets, including the New York Times, the Washington Post, Smithsonian magazine and NPR, hailing the find as a Crusader sword.

In truth, we know very little about the artifact. Archaeology is slow, careful work, and it may be some time before scholars glean any definitive information about the sword. But the international news cycle whirred to life, attaching a charged adjective—Crusader—to a potentially unrelated object. In doing so, media coverage revealed the pervasive reach of this (surprisingly) anachronistic term, which gained traction in recent centuries as a way for historians and polemicists to lump disparate medieval conflicts into an overarching battle between good and evil, Christianity and Islam, civilization and barbarism.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/78/e6/78e66cd9-801d-4657-9bf0-def9510d15b7/1873752469.jpeg)

Although some scholars (including one of the authors of this piece) have argued that we need to do away with the term “Crusades” entirely, most understandably still feel it has value as a category description of a group of complex, interrelated series of Christian holy wars. But the term should never stand alone as an explanation in and of itself. Crusades were waged by Christians against Muslims, Jews and fellow Christians. They were launched in the Middle East, in the Baltic, in Italy, in France and beyond. In the case of the newly discovered sword, we must remember that not every person in the Middle Ages who traversed the seas off the coast of what’s now Israel was a Christian, and not every person who was a Christian at that time was a “Crusader.” By claiming the weapon as a Crusader artifact, the IAA has framed the find (and the period of the sword’s creation) as one of intractable violence and colonialist pretensions.

But the past is messier than that.

The term Crusades, as it’s understood by most modern audiences, refers to a series of religious wars fought by Muslim and Christian armies between 1095 and 1291. It’s a long and fascinating story, dramatized in games, movies and novels and argued about by historians like us. The basics are clear, but the significance is contested. In 1095, Pope Urban II delivered a sermon that launched a disorganized series of campaigns to conquer the city of Jerusalem; against all odds (and in no small part because the various Muslim-ruled states of the area were so disorganized), the city fell to conquering armies from Europe in 1099. Victorious leaders promptly divided up the territory into a small group of principalities that modern European historians have often called the “Crusader states.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a5/86/a586773f-a9cf-4388-91c3-b79522962ee8/councilofclermont.jpeg)

Crusading, or the idea of taking a holy vow to engage in military activity in exchange for spiritual reward, was refined over the next century, redirected to apply to whoever the pope decided might be an enemy of the faith (polytheists and Orthodox Christians in the north, Muslims in Iberia, heretics or rival European Christian powers in France and Italy). In the Middle East, Jerusalem fell back into Islamic hands with the conquest of the city by the famed sultan Saladin in 1187. The last “Crusader” principality on the eastern Mediterranean coast, based out of the city of Acre, fell to the Mamluk ruler Baibars in 1291.

The Crusades weren’t the only events happening during these two centuries in either the Middle East or Europe. Relatively few people were, in fact, Crusaders, and not everything that fell into the eastern Mediterranean Sea during this period was a Crusader artifact. The habit of referring to the “era of the Crusades,” or calling the petty kingdoms that formed, squabbled and fell in these years the “Crusader states,” as if they had some kind of unified identity, is questionable at best. Inhabitants of this part of the Middle East and North Africa were incredibly diverse, with not only Christians, Muslims and Jews but also multiple forms of each religion represented. People spoke a range of languages and claimed wildly diverse ethnic or extended family identities. These groups were not simply enclaves of fanatically religious warriors, but rather part of a long, ever-changing story of horrific violence, cultural connection and hybridity.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/78/1e/781eaa17-8ca7-4af2-8c7a-fa8b54815fad/siegeofacre1291.jpeg)

When Stephennie Mulder, now an expert on Islamic art history at the University of Texas at Austin, was in graduate school in the early 2000s, she took part in a dig searching for Roman artifacts in Tel Dor, Israel. “At that time,” she says, “anything medieval was automatically just called ... ‘Crusader.’” Mulder, who was already thinking about focusing on medieval archaeology within Muslim-ruled states, says, “I was floored by that.” The team unearthed a number of ceramics—important artifacts, but not what the excavation was looking for. Instead, the objects clearly belonged to the period of the Islamic Mamluk sultanate. They were “kind of just put into a box [and] called ‘Crusader,’” says Mulder. “I don't know if [the box] was ever looked at again.” She adds, “In calling this period ‘Crusader,’ Israeli archaeology had, in some ways, aligned itself with a European colonial narrative about the Middle East” that privileged the experience of Europeans over those of locals.

Whether the decision to center this discovery within this frame was conscious or unconscious is difficult to discern. The term “Crusade” has always been an anachronism—a way of looking back at complex, often disconnected movements with a wide array of motivations, membership, tactics and results and organizing them into a single coherent theology or identity. As Benjamin Weber of Stockholm University explains, the phrase “opened the way to complete assimilation of wars fought against different enemies, in varied places and often for similar reasons. ... [It] took on a legitimizing function. Any contested action could be justified by dubbing it a ‘crusade.’ It, therefore, became a word used to wield power and silence denouncers.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/34/db/34db7c43-4d59-49f1-9358-22a896694ba5/dt202036.jpeg)

The word “Crusade” came into use late, long after medieval Christian holy wars began. The Latin word crucesignatus, or “one marked by the cross,” first appeared in the early 1200s, more than a century after Urban II’s call to action in 1095. In English, “Crusade” and “Crusader” don’t appear until around 1700; by the 1800s, the term—defined broadly as a military campaign in defense of one’s faith—had become a convenient way for Victorian historians to mark the past as a battle between what they saw as good and evil, represented respectively by Christianity and Islam. These claims worked especially well as supposed historical justification for contemporary European colonialism, which used rhetoric like “The White Man’s Burden” to paint land grabs as civilizing crusades against “uncivilized” non-Westerners.

Today, the terms “Crusader” and “Crusade” latch onto a nostalgic vision of the past, one that suggests there was a millennia-long clash of civilizations between Islam and Christianity (or “the West”). This is what we have elsewhere called a “rainbow connection”—an attempt to leap over intervening history back to the Middle Ages. But as we argue in our new history of medieval Europe, The Bright Ages, the Crusades weren’t waged solely against Muslims. More importantly, the Crusades ended, ushering in a period of independence and interdependence between Europe and the Middle East. To use the term “Crusader” uncritically for an archaeological discovery in the Middle East is to suggest that the Crusades were the most important thing that happened in the region during the medieval era. That’s just not that case.

The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe

A lively and magisterial popular history that refutes common misperceptions of the European Middle Ages

Instead of labeling all potentially relevant finds “Crusader,” historians must develop terminology that accurately reflects the people who inhabited the Middle East around the 12th century. A potential alternative is “Frankish,” which appears routinely in medieval Arabic sources and can be a useful “generalized term for [medieval] Europeans,” according to Mulder. It initially had pejorative connotations, being “kind of synonymous with a bunch of unwashed barbarians,” she says. “But as there come to be these more sophisticated relationships, it just becomes a term to refer to Europeans.”

This new phrasing is a start, Mulder adds, but even “Frankish” has its problems. Between the 11th and 13th centuries, “hybridity [in the region] is the norm. The fact that another kind of group [establishes itself in the same area] is just part of the story of everything. It's always someone. ... If it's not the Seljuks, it’s the Mongols, it’s the Mamluks. It’s you name it.” Mulder isn’t denying that medieval kingdoms were different, but she argues first and foremost that difference was the norm. “I sometimes think that the Crusades looms so large in the European imagination that we tend to give them more of a space in the history of that period than they really deserve,” she says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4d/e1/4de12f09-d062-4aaf-811a-ee64eb21756f/taking_of_jerusalem_by_the_crusaders_15th_july_1099.jpeg)

We’ll likely never really know who specifically owned the newly discovered sword. Objects have lives of their own, and the weapon’s journey from ship to ocean floor may not have been its first voyage. But attaching the “Crusader” adjective to the sword matters a great deal because it reveals our own modern assumptions about the object, the region’s past and the people who lived there.

An item like a sword has value. It’s forged with the intention of being passed from hand to hand, taken as plunder, given as a gift or handed down to heirs. In the Middle Ages as a whole, but perhaps especially in this corner of the Mediterranean, objects, people and ideas moved across borders all the time. Let’s celebrate the recovery of this artifact, study it, learn what we can and let it speak to us. Let’s not speak on the past’s behalf with our own modern preconceptions, nor lock in the sword’s identity as a symbol of religious violence. It’s a medieval sword, perhaps of Frankish design. We’ll know more about it soon. For now, let that be enough.

llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll